We lack a language for speaking honestly about suicide because we find the topic so hard to think about, at once both deeply unpleasant and gruesomely compelling. When someone ends their life, wether a friend, a family member or even a celebrity whom we identify with – think about the confused reactions to the deaths of Robin Williams and Philip Seymour Hoffman in recent times (although I suspect we could identify stories exerting a similar effect in any year) – one of two reactions habitually follow. We either quietly think that they were being foolish, selfish and irresponsible, or we decide that their actions were caused by factors outside of their control (severe depression, chronic addiction, and so on). That is, if they acted freely in killing themselves, we implicity condemn them; but if we declare that their actions were constrained by uncontrollable behavioural factors like depression, we remove their freedom.

Agains this tendency, I want to open up a space for thinking about suicide as a free act that should not be morally reproached or quietly condemned. Suicide needs to be understood and we desperately need a more grown-up, forgiving and reflectiv discussion of the topic. Too often, the entire debate about suicide is dominated by rage. The surviving spouses, families and friends of someone who committed suicide meet any attempt to discuss suicide with an understandable anger. But we have to dare. We have to speak.

(…)

Suicide, then, finds us both stangely reticent and unusually loquacious: lost for words and full of them. But any contradiction is only apparent, not substantial. What we are facing here is an inhibition, a massive social, psychical and existential blockage that hems us in and stop us thinking. We are either desperately curious about the nasty, intimate, dirty details of the last deconds of a suicide and seek out salacious stories whenever we can. Or we can’t look at all because the prospect is too frightening. Instead, we peek through the slits between our fingers with our hands on our face, as if we were watching a horror movie. Either way, we are hiding something, blocking something, concealing something through our silence or endless chatter or, indeed, rage.

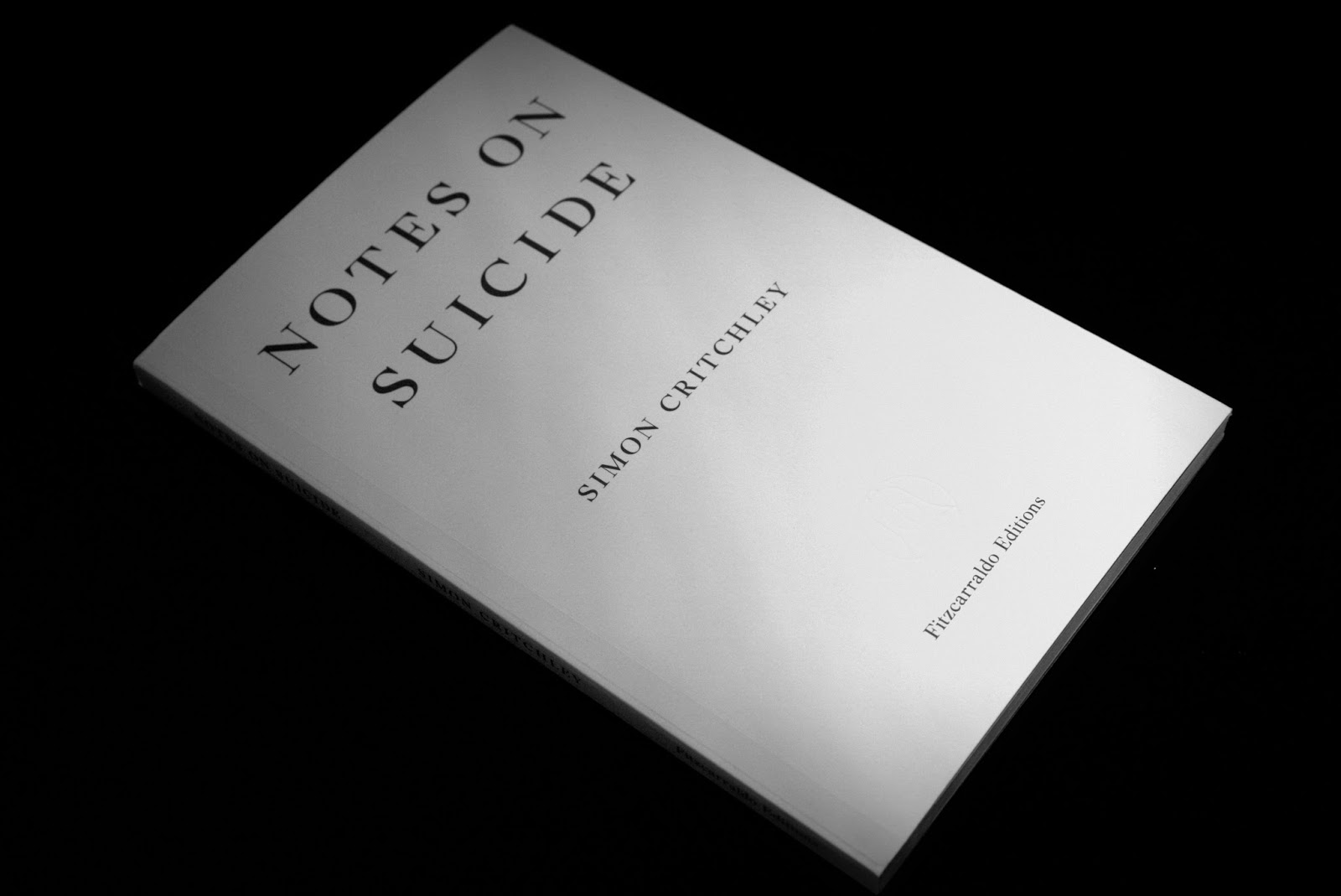

Da última vez que estive em Londres passei no Tate Modern e a recomendação era o I Love Dick, de Chris Kraus. Voltei a cruzar-me com ele desta vez, mas ao lado estava outra recomendação. Este mesmo livro. Comecei o post com excertos que acho relevantes para não desatarem a pensar que enlouqueci ou que estou sequer a pensar em suicidar-me. Como o próprio autor diz, não, isto não é uma nota de suicídio, ou pelo menos não estou a contar que seja. Foram as críticas que encontrei ao livro que me fizeram pegar nele. E fez sentido. Fez sentido porque o suicídio é de facto uma realidade e porque provavelmente toda a gente já teve alguém próximo que se suicidou ou conhece alguém que tinha alguém que se suicidou. Acho que existe realmente um grande tabu e uma grande discrepância de argumentos no que toca a discutir este assunto. Ainda só li umas vinte páginas, mas acho que tudo o que li sobre o livro se confirma. O discurso de Simon Critchley, até agora, é desprovido de dramas e todo argumentado com referências históricas, religiosas, filosóficas e sociais. No final volto a fazer um post sobre o livro com a opinião completa.